Bili Landcare – transforming Westgate Park

The revegetation plan for Westgate Park using indigenous plants was developed by the Friends of Westgate Park not long after their formation in 1999, informed by in-house expertise in botany, planning and gardening and the invaluable Indigenous Plants of the Sandbelt – by Rob Scott and others and the Guide to the Indigenous Plants of the Greater Melbourne Area – Flora of Melbourne – by Marilyn Bull.

Westgate Park – a constructed and then largely neglected landscape of 40 hectares – is now an environmental gem, thanks in large part to this plan.

Background

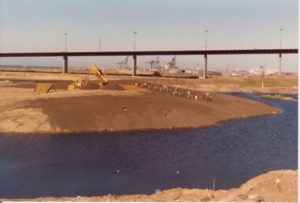

Before it was constructed by the Victorian Department of Conservation, Forests & Lands in the 1980s, the land that is now Westgate Park had been mined for sand, degraded by industrial processes and rubbish dumping and it was used as a construction site for the Bridge. Countless truckloads of demolition waste and soils of all types were brought in from all over Melbourne to shape the park into small hills and mounds, wetlands and lakes. It was initially vegetated with Australian plants but most were not indigenous and either died because they were unsuitable for the Melbourne climate or became weedy. (These have provided limited shelter, especially for birds, and so are being removed only as indigenous plants mature and can take their place.)

For these reasons, revegetation using only the pre-settlement sand dune and marsh vegetation would have been inappropriate.

Instead the plan was to create a diversity of species-rich, bushland habitats that once existed within 5-10 km of the Park at the time of European settlement – South Melbourne and Port Melbourne and along the Yarra to the city – part of the Sand Belt Region of Melbourne.

Plant communities

Nine indigenous plant communities or Ecological Vegetation Classes were identified that would:

- be resilient to climate change

- be attractive habitat for a wide range of birds and insects

- minimise the requirement for ongoing maintenance

- increase the vegetative mass to also capture carbon and help reduce the heat island of central Melbourne

- be a showcase for the amazing diversity of indigenous plants from this region

EVCs were determined by soil, exposure and topography and they transition in a natural manner from Coast Banksia Woodland at the river edge through to Saltmarsh around the salt lakes further inland at Todd Road.

Altogether there are 320 plant species in the Park, many are in several of the nine EVC areas.

Reclaiming nature takes time & effort

The first areas to be planted almost 20 years ago were near the Yarra River and north of the Freshwater Lake. The usual practice is to spot plant large trees and shrubs so that once these mature, the area can be planted out with a diversity of shrubs, grasses, wildflowers and groundcovers that benefit from the microclimate and protection of larger vegetation.

Because little topsoil was used initially, all garden beds are mulched several times over before leaves and bark can build sufficiently to protect the soil and create substrate for beneficial fungi, microbes and insect populations.

Other maturing areas such as the:

- northern red gum woodland

- heath on the north west corner of the Freshwater Lake

- grassy woodland on the hill west of the Freshwater Lake

- grassland just north of the Westgate Bridge crossing

show the potential of indigenous vegetation to provide habitat and a food chain for an astoundingly diverse range of fauna. They also make an attractive floral display in spring and summer.

In recent years around 20,000 plants have been put in the ground each year and more than 300,000 planted since 1999. The vast majority of these were grown by the St Kilda Indigenous Nursery in Williamstown Road, Port Melbourne and the Friends of Westgate Park in their small compound (now combined under amalgamation and called Bili Nursery). For many years now, plants in both nurseries have been propagated from seeds and cuttings harvested from Westgate Park and, as more plants reach maturity and insect populations grow to pollinate them, more can be grown and supplied to other Sand Belt areas.

Some of the many threats to plant survival are drought (the Park is not irrigated), possum and rabbit attack, weed invasion, incorrect soil pH and lack of mycorrhizal fungi.

However, many plants are producing seed in substantial quantities and, with rabbits now under control, thousands are regenerating – a good indication that they will be self-sustaining well into the future.

More planting will be necessary, particularly in those areas most recently added to the Park until perhaps 2021/23 and thereafter, vegetation should only require ongoing maintenance.

See also our page on biodiversity here and our 320 plants in the middle section of the home page.